Administrative Office of Courts

|

Indian Child Welfare Act training explains law and human impact August 28, 2017 Angel Smith was born in 1978, the year Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act. The federal mandate to preserve Native American children’s connections to their families and tribal culture has defined her life.

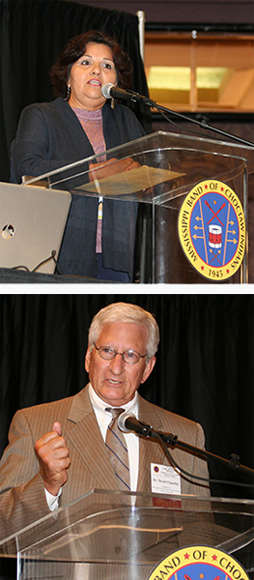

“Had it not been for ICWA, I would not be here today. ICWA matters,” Smith, an Oklahoma attorney and member of the Cherokee Nation, told participants in the Seventh Annual Indian Child Welfare Act Conference Aug. 10 at Choctaw. Smith has devoted much of her law practice to advocacy to enforce ICWA on behalf of Native American children. The annual conference began seven years ago to educate judges, court staff, social workers and other professionals who deal with Native American children in a Youth Court setting. ICWA sets out federal requirements regarding removal and placement of Native American children in foster or adoptive homes. ICWA requirements apply to state child custody proceedings involving any Native American child who is a member of or eligible for membership in a federally recognized tribe. Rae Nell Vaughn, chief of staff of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, said, “It’s important that we continue with the education of our practitioners, our judiciary, our different jurisdictions and our partners.” Department of Child Protection Services Commissioner David Chandler said the many jurisdictions have one vision: “That every child is safe and secure and enjoys a healthy and happy childhood.”  Smith said that she was abandoned at the hospital where she was born and abandoned again at a women and children’s shelter. Her grandmother picked her up at the hospital, but her grandparents couldn’t find her after she was left at the shelter. She was placed in foster care with a non-Native American family. Her mother showed up before her parental rights were to be terminated, and it was determined that Smith was a Native American child subject to ICWA. Litigation over who should have custody – biological family or foster family – went to the Oklahoma Supreme Court twice between 1981 and 1987. She was sent back to live with her mother, where she was again neglected, she said. She went back and forth between her mother and grandparents. As a teenager, she lived with her grandparents in ICWA kinship foster care placement. “Indian children have a right to be with their parents and with their extended family. It’s a right of the child,” Smith said. While she says that her mother failed her, “it didn’t mean that I didn’t have a right to my grandparents, who were good people. That is what ICWA is about.” “It’s not just a legal right. It’s a basic, fundamental human right,” Smith said. Vaughn said, “When there is a thought that a child may be Native American, it’s important to reach out to the Tribe.” There are 558 federally recognized tribes in the United States. The Choctaw Tribe is the only federally recognized tribe in Mississippi. “You treat it as an ICWA case until it’s not an ICWA case,” said Sheldon Spotted Elk. “It’s up to the tribe to decide.” Spotted Elk, a member of the Northern Cheyenne Nation and an attorney, is director of the Indian Child Welfare Unit at Casey Family Programs in Denver, Colorado. Casey Family Programs is the nation's largest private foundation focused on foster care and improving the child welfare system. ICWA cases happen in state courts, Spotted Elk said. Collaboration is necessary to bring about systemic change. “They are building a bridge, not a fence.” A landmark U.S. Supreme Court case that interpreted the enforcement of ICWA came out of Mississippi. The dispute in Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield involved the adoption of twins, born in Gulfport to parents who were residents of the reservation in Neshoba County and were members of the Choctaw tribe. The parents agreed to the twins’ adoption by Orrey and Vivian Holyfield, a non-Native American couple. Two months after the adoption was finalized the Harrison County Chancery Court, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians moved to vacate the adoption, asserting that the Tribal court had exclusive jurisdiction under ICWA. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed. Justice William Brennan Jr., writing for the majority in the April 3, 1989, decision, said, “Three years’ development of family ties cannot be undone, and a separation at this point would doubtless cause considerable pain. Whatever feelings we might have as to where the twins should live, however, it is not for us to decide that question. We have been asked to decide the legal question of who should make the custody determination concerning these children — not what the outcome of that determination should be. The law places that decision in the hands of the Choctaw tribal court.”  Justice Brennan prefaced the Holyfield decision with the history that preceded Congress’ adoption of ICWA, noting that the legislation “was the product of rising concern in the mid-1970's over the consequences to Indian children, Indian families, and Indian tribes of abusive child welfare practices that resulted in the separation of large numbers of Indian children from their families and tribes through adoption or foster care placement, usually in non-Indian homes. Senate oversight hearings in 1974 yielded numerous examples, statistical data, and expert testimony documenting what one witness called ‘[t]he wholesale removal of Indian children from their homes, . . . the most tragic aspect of Indian life today.’ ...Studies undertaken by the Association on American Indian Affairs in 1969 and 1974, and presented in the Senate hearings, showed that 25 to 35% of all Indian children had been separated from their families and placed in adoptive families, foster care, or institutions.”

Spotted Elk, Smith and other conference presenters traced a tragic history from the military’s killing of Indians, to government-sponsored efforts to erase Indian culture by sending children to boarding schools, to the late 1950s Indian Adoption Project’s efforts to adopt Native American children into non-Native American families. Spotted Elk recalled taking his two sons to the site of the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre on the 150th anniversary. His great, great grandfather, Howeche’ Spotted Elk, who was 2 years old, survived the Colorado massacre because an older sibling was told to take him to safety in the creek bed. The November 29 anniversary in his family means the Thanksgiving holiday season is a time of quiet reserve. “I have that undying need to heal,” Spotted Elk explained. “It’s about societal healing.” Tom Lidot said, “ICWA is the first law that was trauma-informed.” “You can’t really do an effective training until you reach someone’s heart,” said Lidot, a consultant with Tribal STAR, Successful Transitions for Adult Readiness in San Diego, California. He is an enrolled member of Chilkat Indian Village, the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indians of Alaska. “History presents tribal folks as a victim or a villain,” Lidot said. “Our approach to training is there is no race of people who are the bad guys....Our opponent is intolerance. Our opponent is apathy. Our opponent is bias.” ICWA’s purpose is to protect the best interests of Indian children and promote stability of Indian tribes and families, Lidot said. ICWA works to keep the child “connected to their family and the tribe. It is part of the restorative justice and the remedial aspect of the law.” Rose-Margaret Orrantia, a tribal elder and member of the Yaqui tribe of Arizona, has spent most of her professional career working with American Indian foster children in California. She emphasized that questions about tribal connections should be asked in foster care placement, termination of parental rights and prospective adoptions. “At every step, you need to be asking the question again,” she said. Parents may not know. Look to grandparents, aunts and uncles and other extended family. Extended family should be considered when seeking family members for placement of children. “When you are looking for those placements, cast that net large,” she said. #### |